24 SepWhat vending machines can teach us about training “come” and “drop it”

Most people think of “dog training” as involving teaching dogs to do what you tell them to do. A well-educated dog should certainly learn that it’s to his benefit if he ultimately complies with your requests, but, if you're just starting to train a dog using what we like to call “Good Dog Training“, you're both still in Kindergarten, and that stuff is high school. First, we are going to train some behaviors where we will be offering good stuff even before the dog does whatever it is you want him to do.

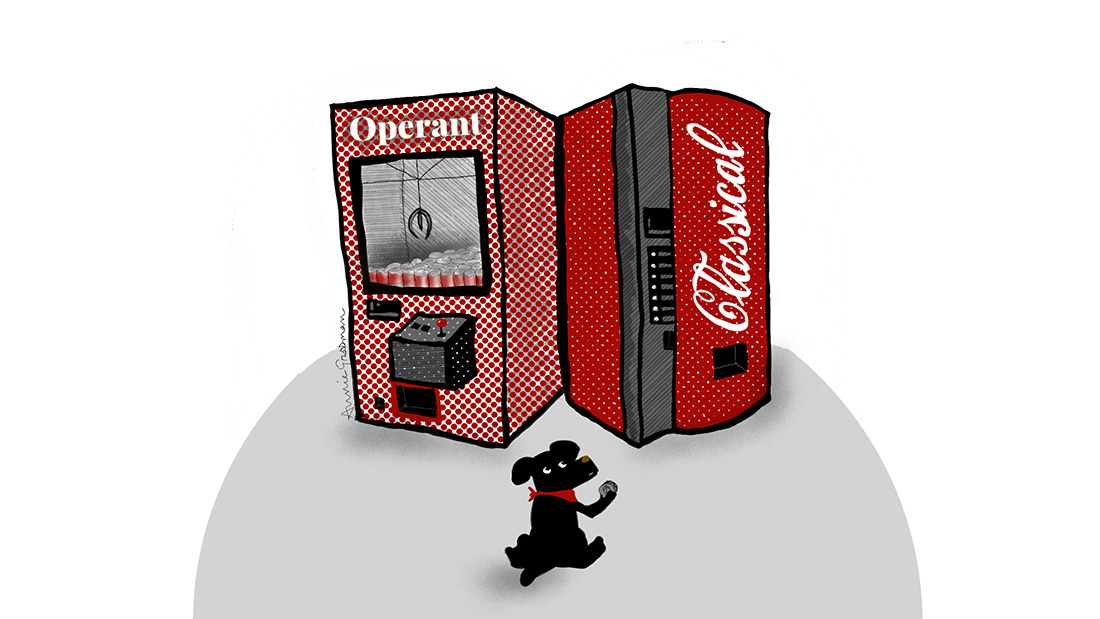

One way to think about teaching a new behavior is like this: imagine two people, each standing in front of a different soda machine. Now imagine we are trying to teach the behavior of emptying out these people’s pockets–a behavior we are all being trained to do constantly.

One soda machine is a regular soda machine: You put in money, and out comes your soda. Sometimes it jams, but almost all of the time, a dollar equals soda.

The other soda machine is set up like a magic claw: One dollar gives you the opportunity to use the motorized crane to maneuver up, down, left and right in order to pick up the soda and navigate it to the slot that will then dispense it to you. (If you are bothered by the fact that this would make for very fizzy soda, redo the mental experiment with bottled water).

So, one machine is a sure thing, where the behavior is irrelevant. Did he put the money in with his left hand or right? Was it a bill or quarters? Who cares! Just like you don’t care if your dog drops something from his mouth onto this part of the floor or that part of the floor, or if he does it by pushing it out with his tongue or opening his jaw. You just want the thing out of his mouth, like the soda company just wants the money. We get the money because our consumer knows that money nets soda, and quickly, too. Plink plunk. If the system breaks on his ninety-ninth try, he will probably shrug it off as a glitch and will keep on spending his money there.

The other machine requires both a degree of skill and luck. Even with excellent hand-eye coordination, you still might only get the soda to the slot every second or third time. And there is a time lag, too. Plink, ggrrrrr, rrrrrr, rrrrr, and then maybe plunk. If I was interested in teaching the man the fine skill of maneuvering a claw crane, then this would be the machine to use. But that wasn’t my goal. I just want him to spend his money, and, preferably, fast.

My choice of machine, therefore, is obvious. In some training instances, using “classical conditioning” in dog training can lead to similarly effective and quick results. Two behaviors in particular can be taught quickly and reliably by focusing on classical conditioning above all us: Those behaviors are “come” and “drop it.”

Drop it

Teaching your dog to drop an item when asked can be very helpful when out on leash walks (if your dog picks up an unsavory item) and is also a behavior all dogs who play tug or fetch should learn — “fetch” quickly turns into “chase” if your dog won’t drop the ball! A human equivalent of this exercise is the term “Huge sale, drop everything!” The store is hoping that you will stop everything else you’re doing and run to the store. It’s a more effective sales method than saying “If you come to my store, maybe I’ll give you a deal.” The latter involves a contingency. The former doesn’t; the sale isn’t happening because of you. When teaching drop it, you’re going to throw a sale.

To start, you will be conditioning your dog to the words “Drop it.” We want him to realize that every time you say it, YOU drop stuff. Have a treat pouch or bowl with a bunch of small treats ready, or have them hidden in your hand. If your dog is distracted, you can do this exercise with him in a pen or in a crate, or tethered. It is crucial that your treats remain out of sight until you say the words. Saying “drop it” and giving the treats at the same time will render the words meaningless, as the laws of classical conditioning requires that the thing that you’re imbuing with meaning (the words “drop it,” also known as the conditioned stimulus) precede the stuff that has innate meaning (food, aka unconditioned stimulus). Pairing in the other direction, or concurrently doesn’t work.

Tools: High value treats and an object your dog likes to have in his mouth, such as a bone or a rope toy.

Step 1: Approach your dog and say “Drop it” just once, in a clear voice and then immediately toss a small handful of treats on the ground in front of your dog. When he has finished eating the treat, repeat again. Repeat this exercise thirty times, over the course of one two sessions. If your dog is starting to look to the ground every time you say “Drop it,” it is time to move on to the next level. If not, keep going through this level until he is.

Step 2: Once he is reliably looking at you or the ground when you say “Drop it,” you can bring out a toy or chewy or something else your puppy likes to have in his mouth. If your dog has a tendency to run away when he gets his toy or chewy, then it’s definitely best to have him tethered or crated or penned for this, as you don’t want to have to chase him in order to start the exercise. Once your dog is engaging with the toy, say “Drop it” and toss the handful of treats on the ground, just as before. If your dog doesn’t immediately drop whatever is in his mouth, use some better treats, give him a less exciting thing to chew on, or do both.

Step 3: Begin inserting a slight delay between your “Drop it” cue and the presentation of the treats. You should still give the treat even if your dog doesn’t drop the thing, but they usually catch on pretty fast. If you’re waiting longer than five seconds between when you say “Drop it” and when he drops the thing from his mouth, make the delay between your “Drop it” and the treat shorter, or try upping the value of your treats.

Step 4: Repeat until your puppy has a strong enough association with the word “Drop” that they release whatever they have. When practicing in a new location, or with a new toy, or with a new person, start the whole exercise from the start each time.

Come

Come is one of the most important things a dog can learn, and it always should be followed by something good. It is a bad idea to ever call your dog to “come” if you’re going to do something he is sure to dislike — “come” is not used when it’s time for, say, bathing or brushing. Your “come” needs to net a party every time, even if you feel like you’re rewarding a behavior that was kind of sucky, or if you feel like you’re doing a jig for him and all he did was take a few steps towards you in a small room. When we teach “come” using classical conditioning, we call it the “special” come because it’s wise to use something distinct your dog will be unlikely to mistake with anything else. For many dogs, I think words are spewed around them all the time to the point where they can turn into static rather than information. For that reason, I think it is a good idea to teach this special come with a non-verbal. If you can use a sound or other signal that will travel a great distance, all the better.

Tools: For this exercise, I like to use a bell or a whistle, as these are distinct sounds that most dogs don’t hear very often. If you’re going to use a word, choose one your dog probably doesn’t hear a lot — one School For The Dogs’ clients says “Godzilla!” because, in her home, he is not a frequent topic of conversation. Of course, if you choose a word, you may also want to pick something you wouldn’t mind yelling in public. (For this reason, Godzilla might not be your first choice). My preference is to use a whistle, as you can hang a few around the house and keep one on your keychain when you’re out. The best is if you are able to whistle really loudly yourself. I hate you.

Any kind of food rewards will work for this exercise — it’s even fine to use bits of ham or other kinds of slimy stuff I don’t usually recommend, since you’re going to have both hands free to deliver the goods. While it’s wise to sometimes practice this with really high value treats, keep in mind that you’ll want to do this exercise frequently. So, if sometimes you’re just using your dog’s regular dry food, that’s fine too.

- Step 1: Go to your dog, with treats hidden in your hand and your whistle in your mouth. Your dog should be no more than two feet away. Blow the whistle (one blow, or two or three swift ones — doesn’t matter as long as you’re consistent each time). Then drop treats at your feet. You don’t have to drop just one. This is an exercise where you are allowed to reward your dog in a stupidly generous way for doing next to nothing. “But he didn’t even come,” you say. “He was already at my feet!” I know! Doesn’t matter! That’s how easy this needs to be. Was he existing? Yes? He deserves a treat Bar Mitzvah.

- Step 2: For one week, practice the above level, a minimum of fifteen times a day in at least three different familiar places. This should take no more than a minute a day, and it should be incredibly easy for your dog. Of course you could do more. If you want to, you could feed an entire bowl of kibble in this way. Just make sure you are not showing the treat until after you whistle.

- Step 3: Toss a treat five feet away from you, in a familiar place. The first treat is a total freebie. When your dog gets the treat, blow the whistle, and then drop a treat at your feet. Repeat for a week, a minimum of fifteen times a day in the same locations as before. If your dog is reliably running back and forth between you and the tossed treat whenever he hears the whistle, start tossing the treat ten feet away, then whistling and delivering one at your feet. If your dog seems to not be getting the picture, go back to Step 1.

- Step 4: Once you get to the ten foot point, try tossing the treat five feet and then running five feet in the other direction while he goes for it. Whistle when you arrive at your destination five feet away, and then deliver the treat five feet away in the other direction, again running the opposite way and then whistling when you get to you are again five feet away. At this level, you’re adding speed to the game, and your building excitement. Now he is getting to run for the treat, and chase you, and get another treat. Best game ever!

- Step 5: Once you are working the fourth step, you can concurrently go back to Step 1, now doing it in three new locations.

- Step 6: Furnish a friend with treats and a whistle, and stand ten feet away from each other in one of your original locations. Take turns blowing the whistles and then tossing treat at your feet. If this is confusing to your dog, have your friend move closer to you until your dog is eager to run back and forth in between you.

- Step 7: Have your friend start running ten feet in the opposite direction right after your dog gets treats at your feet. She should then blow the whistle and do the treats-at-feet thing.

- Step 8: Increase distance! You can also start grabbing your dog’s collar while he eats the treats he receives when he gets to you. There may be times when you will need to take hold of him when he gets to you, and this is a good time to help him create a good association with that sensation.

Remember: You are never working your dog to a point of failure in this exercise. If, at any point, he seems to be uninterested in the exercise, either postpone the training session, go back to the prior level, or try using better treats or both.

Make sure to to check out our podcast episode on this topic!