14 JulThe Dog Training Triad Part 1: Management

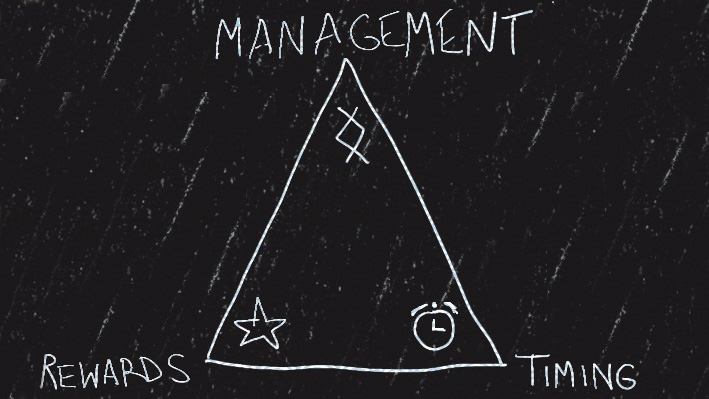

There are three major ingredients required in any positive reinforcement-based dog training plan. They are: Management, Timing, and Rewards. We call this The Training Triad. In this series of posts (and accompanying podcast episodes–click here or scroll down to listen) we will be talking about each of these essential pillars.

There are three major ingredients required in any positive reinforcement-based dog training plan. They are: Management, Timing, and Rewards. We call this The Training Triad. In this series of posts (and accompanying podcast episodes–click here or scroll down to listen) we will be talking about each of these essential pillars.

What is “management” in dog training terms?

Simply put, management is all about making the right option the easy option for your learner in order to up the chances of getting the behaviors you want.

We govern our dogs’ worlds, and a great way to get behaviors we want is to not allow the behaviors we don’t want to ever occur to begin with. In someways, there are lots of ways in which we are smart about managing our dogs' behavior without even thinking about. How do you make sure you don't get the behavior of your dog running into the street? You keep your dog on a leash. How do you keep a puppy from peeing on the rug? Pick up the rug. A crate is, for example, a very useful management tool, as a dog who is in a crate simply cannot also be chewing on your coffee tables' legs, or pooping on the sofa.

But isn't training more complicated than that?

Managing the environment in order make sure behaviors you don't want don't occur is often the “oh, duh” kind of dog training solution that will leave you kicking yourself for not having thought of it yourself. Usually, it mostly involves training humans. Don’t want your dog to drink from the toilet? Close the lid. Don’t want dog to chew shoes? Put them in the closet, and keep the door shut. The fact that environmental management can be easy should be happy news: Good dog training doesn't need to be hard!

Keep bad behaviors from ever starting

As a trainer, it is always preferable to smartly consider how to set the stage to optimize chances of success rather than rearranging the environment after your pupil has already done something you don't want him or her to do. This is because:

-An unwanted behavior could be one that is life threatening. Would you rather your dog chew on a wire so that he learns a lesson, or do you want him to not do it in the first place? Do you put a fence around the pool before or after your toddler winds up flailing in the deep end?

-If an unwanted behavior occurs, there is a good chance it will be reinforced just by the doing of it, and reinforced behaviors are, by definition, more likely to occur again in the future. Peeing on the rug feels good. Chewing on a wire feels good. Barking feels good. Whenever your dog has the option to do one of those things, he or she will only be getting better at doing it. So, even if you rearrange the environment so the behavior won't happen again, it still has some reinforcement history behind it, which could affect future behaviors in a new environment. For instance: If someone is jailed because he shoots someone who was blackmailing him, the behavior of shooting a person was probably reinforced because it made the blackmailer go away. We can manage that person's behavior by putting him or her in a prison where guns aren't accessible, but the behavior of murdering someone was still probably reinforced, and some version of that behavior is therefore more likely to happen again — at least it's more likely to occur again than if there had been no murder to begin with. What's more, a variable rate of reinforcement can be a powerful motivator, so even if a behavior is only reinforced once, it may still reoccur because your subject will be waiting for the next jackpot: For instance, your dog may get a chicken thigh off the kitchen counter just one time before you vow to never ever leave food unattended on the counter again… but the dog will probably continue to check the counter, with the hopes that one day lucky just might strike again.

-Once you have a behavior you don't want, you'll either have to rethink your management plan in order to make sure the behavior cannot happen again (which can be hard, as outlined above in the murder and kitchen counter examples), or punish the behavior in order to discourage the likelihood it'll happen again. But attempts at using punishment can be problematic for a number of reasons. Among them:

- Often we yell at dogs to punish them, when in fact they frequently find any attention to be rewarding. If your punishment has truly been effective, you should know because the incidences of the behavior occurring should decrease to the point of not happening any more. If you're yelling at your dog every day for doing the same thing, yelling is probably not an effective punisher.

- The dog might associate the wrong thing with the punishment you wield. For instance, the dog might think that peeing in front of you is bad rather than peeing on the rug is bad; he might think that eating something off the curb is bad but eating something in the middle of the street is fine, etc.

- Dogs can become desensitized to punishment, meaning that you'll have to continually raise the severity of the punishment (this is one reason why shock collars have multiple levels of intensity), and sometimes you might hit a limit of how much more you can punish something. Because it is sometimes helpful to look at these things at their extremes, let's take the murder example again: Say the punishment for murdering someone is the death penalty. In that case, how do you punish the person who murders someone while on death row? Or a less extreme example: How to you punish the kids in the Breakfast Club for their antics when they already have detention!

- The inherent reinforcement of doing the unwanted behavior may be much greater than any kind of punishment could dream up. Here's another 1980's movie example: The amount of fun Ferris Bueller had on his day off exceeded any possible punishment he figured he could receive for missing school.

Create a “Yellow Brick Road”

The boundaries we create for our dogs shouldn’t be set with barbed wire. Rather than dogs to be on the path we want them to be on, we need to make the path really awesome so they have no reason to veer. Think about Dorothy and her crew on the Yellow Brick Road: They weren't forced to stay on the road, but they remained on it because there were lots of good things happening on that path. As trainers, we can create that road. Outside of the road is where options exist like chewing up your mouth guard, and barking at every sound in the hallway. Ever notice there is a red brick road next to the yellow one that Dorothy trod? She probably didn't notice it either! What may have the Red Brick Road contained? Some guesses: A heroin dealer, a tattoo parlor and an OTB.

But Dorothy never discovered those delights, just like your dog may never engage in behaviors that he doesn't know are possible. By controlling their world from the outside, we can help boost the chances we’re going to get dog behaviors we really like — then we can positively reinforce those behaviors like crazy in order to increase the likelihood that they will reoccur.

The Management Recipe: Space, Time, and Energy

There are three things we are managing in training. Here are some tools and tips to consider to help you manage these elements wisely.

MANAGING SPACE:

So much behavior is the result of the physical space we inhabit: Just think about how much of your behavior is dictated by the buildings you occupy, the design of the objects you use and the structure of the city or town you live in. Here are some tools we can use to literally alter a dog's environment in order to manage their behavior.

Crates

A dog who is in a crate has a limited repertoire of things to do. Your crate should be not much bigger than your dog; some come with dividers so that you can make it bigger as your dog grows. Dogs do not usually like to hang out in their pee and poop, so the likelihood that your dog will eliminate inside is reduced if he or she is crated. He or she also cannot develop the habit of chewing inappropriate things when alone if he or she is confined and can’t access those things.

A bag can be a management tool that will help you know exactly where you dog is, and what he or she is doing.

Alternatives to crating include carrying a dog in a bag, or keeping him tethered to you.

While some might feel its cruel to limit a dog's space, a dog can be conditioned to enjoy being in a crate, and, in the crate, the dog can do lots of things that he or she may find enjoyable: You can give you dog toys and meals in the crate, and you can do training with your dog in the crate. It's not unlike putting a child in a school: Part of the reason we usually put kids into a physical school building during the day is so that we know where they are, and we can be assured they are not doing all the many possible things they could be doing if they were anywhere other than in that confined, monitored space. (See the aforementioned Red Brick Road activities… or watch Ferris Bueller's Day Off!).

However, ideally, school should be a place where lots of enjoyable things are happening — a place where a kid wants to be, just like, ideally, we want our dogs to like being in their crate. See this post for more on crate training.

Muzzles

Although often associated with dogs who have a bite history, a muzzle can be a useful tool to keep a dog from ever biting anyone to begin with. Biting isn't just the terrain of vicious dogs: Any dog who has teeth is capable of biting, especially when provoked, stressed, or in pain. Just like a crate, a dog can be conditioned to be okay wearing a muzzle, and using one as a precaution when you know your dog might be extra stressed can keep a bite history from ever developing. What's more, a muzzle can be a good management tool to keep a street scavenger from eating sidewalk trash.

White noise machines

In addition to physically managing environments, we can also manage stimuli in a space to make sure that unwanted behavior don't occur. For instance, if you have a dog who is easily triggered to bark by random sounds, a white noise machine can drown out noises in the hallway, as can a door sweep that you can put under your door.

MANAGING TIME:

Dogs spend at least 50% of their time sleeping. Puppies, it’s closer to 80%. For a youngster, that can mean that there are only four or five hours in the day that he or she is actively doing stuff. If we can fill that relatively small amount of time with appropriate activities, your dog will be less likely to take an interest in undesirable extracurriculars. When it comes to managing time, it's important to make sure of two things:

- You're scheduling your dog's day in such a way that he or she will eliminate where and when you want.

- You're making meal times literally last as long as possible. More on this below.

The Northmate Green Feeder is a “work to eat” toy that can extend the amount of time mealtime takes.

MANAGING ENERGY:

A dog’s energy isn’t infinite! If you can help your dog use it in appropriate way, he or she will have less mojo available to do things you don’t like, such as laps on your couch or redesigning your coffee table with his or her mouth. Make sure your dog gets exercise doing things that you like. That might mean going for long walks or runs, playing tug, or attending classes or playgroups. Food also plays a part in this. Finding the right food for your dog can affect his physical and mental health, and increase (or decrease) the likelihood that he will do things you want him to do.

One great way to manage a dog's energy is to make sure he or she eats all, or at least some, of his meals from work to eat toys. These are toys that are designed to engage your dog's brain while he eats, and to literally extend the time that meal time takes. The more time and energy is expended on excavating food from a toy, the less time and energy will be available for possibly destructive activities.

This post is part one of a three part series on The Training Triad. Stay tuned for our next posts, which will be on rewards and timing. Make sure to check out our podcast for accompanying content.

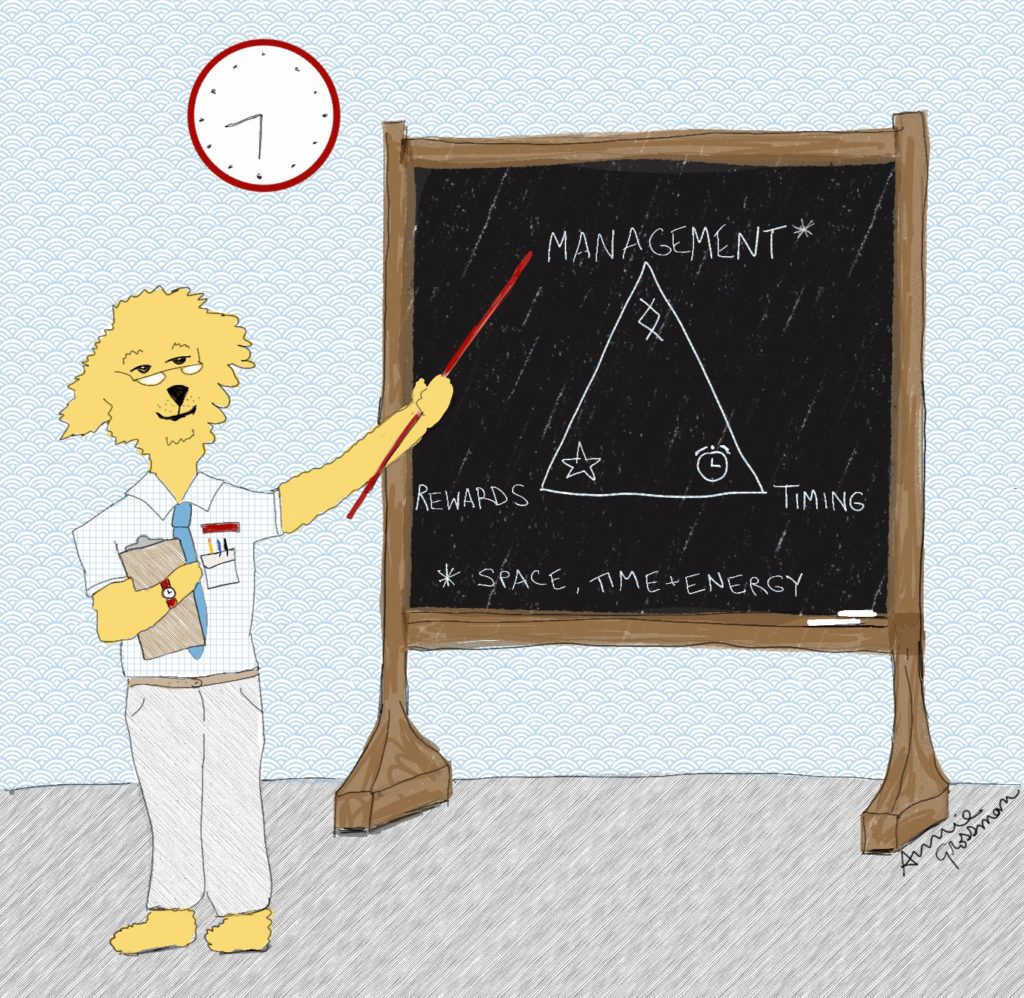

Featured drawing by Annie Grossman